Today I’m going to write a bit about the shape of time, a big topic which I’ll need to come back to a number of times to discuss specific examples. Consider this an overview of the topic, which follows on from my last post’s discussion of circular and linear time. In particular, today I’m going to focus on how we use space to think about time, where we locate different times in our mental landscapes. It turns out that this is not as straightforward as it might at first seem, and there is plenty of variation.

Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (Wikipedia)

The first thing we need to cover is the idea that we need to use metaphor to think and speak about time. Time is an abstract idea. We have no direct way of perceiving time, no sense devoted to it. There are, of course, workarounds to this, and in fact in many cases we’re quite good at estimating the kinds of timeframes we tend to have to deal with in day-to-day life. It seems the brain has no one internal clock, though there are regions of the brain that control things like the circadian rhythm (specifically in that case the roughly 20,000 neurons collectively known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus), and it has been suggested that the number of things we experience and the number of memories we create affects our judgement of the duration of time. We are also able to perform motor tasks that require very precise timing, and can judge the minute time difference between sounds coming in one ear and the other in order to have stereo location of sounds. However, our experience of time can also be quite flexible, as Claudia Hammond discusses in her book Time Warped (which I’m working my way through right now). In any case we have difficulty thinking and talking about time without relating it to something else, as suggested by the passage I quoted from St Augustine a couple of posts ago.

suprachiasmatic nucleus and circadian rhythms (Wikipedia)

It is frequently noted then that we use metaphor to talk and even think about time, metaphor particularly drawn from the concrete domain of space, to think and talk about the very abstract domain of time. Indeed that’s generally the way it works, according to George Lakoff and Mark Johnson in their groundbreaking book Metaphors We Live By — we constantly use metaphors drawn from very concrete, experiential domains in order to think about all the more abstract domains, and we can’t get very far without doing this. Language, and indeed thought, is essentially metaphorical once you get past the concrete and the physical. Space is one of the first things we perceive and experience in life. As babies we soon learn spatial relationships, first learning to make sense of visual data, such as the arrangement of features on a face, and then interacting with the spatial domain as we become able to move through it. Thus unsurprisingly we use spatial metaphors to deal with a whole host of more abstract ideas.

It has been suggested, by Lakoff and Johnson as well as by many others, that all people, cultures, and languages draw on space to deal with time, though it has recently been argued that speakers of the Amazonian language Amondawa don’t do this space-time mapping at all (and indeed they may do very little abstract thinking about time at all, the research suggests). In any case, though most languages draw on space to talk about time, not all cultures/languages arrange time in the same metaphorical spatial relations.

In English, we’re accustomed to talking about time in what is called a sagittal axis, that is back to front relative to our bodies, with the future in front of us and the past behind. But this isn’t the only possible mapping of time onto space. There are some languages that locate the past in front and the future behind, due to the fact that we know what has already happened, but can’t “see” the future. This has long been suggested of Ancient Greek, with the following comment on the word ὀπίσω ‘backward’ in the standard 19th century Greek lexicon by Liddel and Scott: “of Time, hereafter, since the future is unseen and was therefore regarded as behind us, whereas the past is known and therefore before our eyes”. A similar claim has been made of the Madagascar language Malagasy (according to Øyvind Dahl), and other languages as well. While there has been some criticism of these claims, Núñez and Sweetser very convincingly demonstrate that this is the case in the South American language Aymara. The nice thing about their research is that they draw not only on linguistic evidence of this metaphor, but gestural evidence as well. I’ll discuss these examples at more length in a later post.

body planes, including the sagittal axis (Wikipedia)

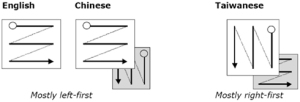

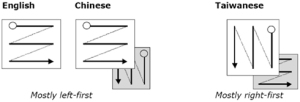

English speakers also tend to use a left-to-right arrangement for time as well, with the past to the left and the future to the right. Though we never use left-to-right metaphors in speech — you don’t for instance say Boxing Day is right of Christmas — test subjects will tend to arrange temporally ordered pictures in this direction and more quickly recognize temporal orders if consistent with the left-to-right arrangement. This temporal arrangement seems to be influenced by writing direction, with Hebrew speakers showing the opposite right-to-left arrangement consistent with their writing direction. Mandarin speakers tend to more often use an up-down arrangement for time, consistent with their writing direction (at least sometimes and in some places, particularly in Taiwan, but more on that in a later post), and even use up-down metaphors in speech, with above being earlier and below being later. Though I’ve never seen it suggested in any of the research, I wonder if the mechanism for this kind of directionality is not so much the writing direction itself, but at least in part the arrangement of book mechanics. In English books we read the left page and then the right one, and then turn the page to the left. Even before they can read, children master the mechanics of a book, based on the pictures and the turning of the pages by whoever is reading to them, and thus they are trained into understanding narrative, and thus time, as progressing in that particular direction. Of course the arrangement of a book, left to right or right to left, is at least in part influenced by writing direction, but it seems to me to be worth researching what the effect of book direction is, looking for instance at up-down languages like Mandarin to see if there is a secondary left/right bias based on page turning direction. Furthermore, we can consider narrative conventions — in film, it seems to me, journeys out are more often depicted as going toward the right and journeys home towards the left. Look for this next time you watch a science fiction tv show or movie like Star Trek, with journeys away from earth more often depicted towards the right. And what are the cinematic conventions in other cultures?

writing directions of English, Mainland Chinese, and Taiwanese (Bergen & Lau 2012)

An even more striking example of a different spatio-temporal arrangement can be found in languages that use absolute spatial terms, such as cardinal directions (north, south, east, west), rather than body-relative ones, as in English right and left. The Pormpuraaw languages of Australia, for instance, such as Kuuk Thaayorre, are such languages. Speakers of these languages are always aware of their absolute spatial orientation, since they always have to use these absolute terms to refer to any spatial arrangement. Essentially they would, for instance, have to refer to their north leg rather than their right leg. Furthermore they draw on this spatial reasoning for reasoning about time, always arranging pictures in temporal order east to west regardless of the orientation of their own body, clearly mirroring the course of the sun in the sky. And there are a variety of other shapes and spatial arrangements for time as well, such as concentric, near and far, up and down hill, and so forth. More on these later.

some temporal arrangements (Bergen & Lau 2012)

There is one last issue relating to our spatio-temporal arrangements I’d like to mention today: how movement is used to think about the passage of time. One can think of either time moving, as if you are watching a river flow towards you, for instance, as in “the holidays are approaching”, or ego-moving, as if you yourself are moving along a path, as in “we’re rapidly coming to the end of the year”. In English, both of these metaphors are available, though this isn’t necessarily true in all languages. And it turns out, you draw on spatial reasoning actively, so that if you are already predisposed to thinking of yourself moving in space, by say going on a journey, you are more likely to think of yourself moving through time. This sort of thing can affect how we interpret ambiguous phrasings such as the sentence “let’s move Wednesday’s meeting back two days”. Does this mean the meeting is now on Monday or Friday? It depends on whether you are thinking from a time-moving perspective or an ego-moving perspective.

time perspective (Boroditsky 2000)

So that’s a bit of an overview of some of the issues relating to how we use space to think about time. I’ll come back to a number of these examples that I’ve mentioned here and discuss them in more detail in future posts, along with some other interesting cases that I haven’t yet mentioned. The upshot of all this is that we think about time in very different ways, depending on language and a variety of other cultural influences. There seems to be great variation in human temporal cognition. Try to pay closer attention to the ways you talk about time and the kinds of metaphors or expressions you use (not necessarily just spatial ones), and don’t assume these are universal and shared by everyone. It’s endlessly fascinating.

A select bibliography because making footnotes in WordPress is irritating and I’m getting lazy (and sorry about the messiness and inconsistency here, but again I’m feeling lazy):

Bergen, Benjamin K. “Writing Direction Affects How People Map Space onto Time.” Frontiers in Cultural Psychology 3 (2012): 109. Frontiers. Web.

Boroditsky, L. “Does language shape thought? English and Mandarin speakers’ conceptions of time.” Cognitive Psychology 43.1 (2001): 1–22.

Boroditsky, L., Fuhrman, O., & McCormick, K. “Do English and Mandarin speakers think differently about time?” Cognition (2010), doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.09.010

Boroditsky, L. & Gaby, A. “Remembrances of Times East: Absolute Spatial Representations of Time in an Australian Aboriginal Community.” Psychological Science (2010), doi:10.1177/0956797610386621

Dahl, Øyvind. “When the Future Comes from Behind: Malagasy and Other Time Concepts and Some Consequences for Communication.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 19.2 (1995): 197-209.

Gaby, Alice. “The Thaayorre Think of Time Like They Talk of Space.” Frontiers in Cultural Psychology 3 (2012): 300. Frontiers. Web.

Guen, Olivier Le, and Lorena Ildefonsa Pool Balam. “No Metaphorical Timeline in Gesture and Cognition Among Yucatec Mayas.” Frontiers in Cultural Psychology 3 (2012): 271. Frontiers. Web.

Hammond, Claudia. Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception. Canongate Books, 2012. Print.

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: Chicago UP, 1980.

Núñez, Rafael E. & Sweetser, Eve. “With the Future Behind Them: Convergent Evidence From Aymara Language and Gesture in the Crosslinguistic Comparison of Spatial Construals of Time.” Cognitive Science 30 (2006): 401-450.

Sinha, Chris et al. “When Time Is Not Space: The Social and Linguistic Construction of Time Intervals and Temporal Event Relations in an Amazonian Culture.” Language and Cognition 3.1 (2011): 137–169. Print.